I’ve recently come to realize that you can never have too many fathers. Milton Klein was my third father, and my last.

Every dad brings something new and worthwhile into your life. Milton brought an intense interest in world events—whether they were political events, natural, technological, or accidental events—and their impact on humanity, on humankind.

In this way, Milton was a lot like one of my many grandmothers, the one named Evelyne.

With Milton, though, it wasn’t just that he was curious about events in the world. More than that, he worried about them.

I met Milton in 1986—thirty years ago—soon after Karen and I started dating. At the time, if my memory is right, Milton was worried about Chernobyl. Well, fine, everyone was worried about Chernobyl.

(Now, I should point out that Milton also worried that I wouldn’t be able to care for his daughter when she had the flu. Here I am, rushing to Karen’s bedside, the devoted boyfriend, but Milt and Roz are already there, with the vaporizer, the chicken soup. Feeling pretty pleased with themselves.)

Anyway … Karen and I still got married, in 1987. When we got back from our honeymoon, Milton was worrying about “Black Monday,” the October stock market crash.

In 1989, Matthew was born. Milton was worrying about the long-term effects of the Exxon Valdez oil spill. He was overjoyed about his first grandchild, until he heard about the Tiananmen Square massacre, but he cheered up later in the year when the Berlin Wall came down.

When Zoë joined our family in 1994, Milton was worrying about genocide in Rwanda and ethnic cleansing in Bosnia. He welcomed Zoë home at about the same time that Nelson Mandela became president of South Africa. Soon after, Milton began to worry again, about Newt Gingrich and the Republicans taking over Congress.

And on it went.

The thing is, all the worrying, all the anxiety, it bound us together, Milton and me—the fraud and hype of the dot-com bubble, the fathomless disaster of the George W. Bush years—and soon enough, I started to worry about world events too.

We would sit and have these long conversations about the news of the day. The kind of conversations that would end with Karen coming in and saying, “you two finished saving the world yet, or what?”

We were not finished.

Well, that’s it, then, Milton. You were the last dad standing. I love you, buddy. I love you, even if you left me here to worry about Donald Trump all by myself.

| First of all, fuck PolitiFact. Facts are binary. Politics are manifold. |

All politicians lie. And usually, when politicians lie, what they lie about is the necessity, rationale or purpose of some public policy that they support. Particularly when a President lies, the only citizens who get angry are those who disagree with the policy—the policy whose actual necessity, rationale or purpose the lies are intended to keep hidden. Citizens, and especially political elites, who agree with the policy implicitly endorse the President’s lies as necessary to convince an unsophisticated, insufficiently farsighted, or selfish public.

Two examples:

Elite supporters of the Iraq invasion and Obamacare, respectively, knew that the President was lying, but cared more about getting the policy enacted than they cared about the truth. This was because the necessity, rationale or purpose of the policy, from the elite supporters’ perspective, was fundamentally not a necessity, rationale or purpose that could be sold to the American public. Citizens, by and large, were uninterested in sending our troops to the Middle East to eliminate a potentially threatening (but for the moment purely local) tyrant, just as they were uninterested in sacrificing their own privileges in order to provide all Americans with universal health insurance coverage. In both cases, the President’s elite supporters had a more “enlightened” view, but one that dared not speak its name.

A President tells whoppers because political elites want him to tell whoppers, as a means of enacting a policy they support. And this drives opponents of the President’s policy crazy, not least because the lies do the job of convincing the public and, instead of the President being punished for lying, the lies only make him appear more successful. The President’s policy may ultimately fail, but usually not because the President lied about its necessity, rationale or purpose. More often, it’s because the policy’s actual, hidden necessity, rationale or purpose—the perspective of the President’s elite supporters—itself turns out to be wrong or unachievable in practice.

The Iraq invasion failed because we were not, in fact, greeted as liberators. It didn’t matter that Saddam wasn’t really trying to produce nuclear weapons. If Obamacare fails, it will be because large numbers of disadvantaged Americans continue to have inadequate health insurance coverage. It won’t matter that those insured prior to Obamacare really weren’t able to keep their plan of choice.

My conclusion: political lying—at least at the Presidential level—is not only costless, but greatly enhances a President’s rhetorical and persuasive powers in a deeply divided country. It also works to the manifest advantage of political elites. But then again, what doesn’t?

Bret Stephens’ column in The Wall Street Journal today doesn’t begin well:

Years ago I had a chat with three young Muslim men as we waited in a Heathrow airport lounge to board a flight to Islamabad. I was going to Pakistan to report on the fallout from a devastating earthquake in Kashmir. They were going there to do what they vaguely described as “charitable work.” They dressed in white shalwar kameez, wore their beards in salafist style and spoke in south London accents.

I tried to steer the conversation to the earthquake. They wanted to talk about politics. Had I seen Michael Moore’s “Fahrenheit 9/11”? I avoided furnishing an opinion about a film they plainly revered. The unvarnished truth about Amerika—from an American. Authority and authenticity rolled into one.

I think of that exchange whenever the subject of Islamist radicalization comes up.

Uh oh, the Tom Friedman notional-man-on-the-street formula. And then, this:

[T]he influence of the [Anwar al-]Awlakis of the world can’t fully account for the mind-set of these jihadists. They are also sons of the West—educated in the schools of multiculturalism, reared on the works of Noam Chomsky and perhaps Frantz Fanon, consumers of a news diet heavy with reports of perfidy by American or British or Israeli soldiers. If Islamism is their ideological drug of choice, the political orthodoxies of the modern left are their gateway to it.

Wait. Haven’t we always been accused of avoiding the obvious by not calling it “Islamic terrorism”? But suddenly Islam “can’t fully account for the mind-set of these jihadists”? What, now we’re supposed to call it “progressive left, multicultural, anti-war Islamic terrorism”?

[The language used by al Qaeda in Yemen in its online publications] isn’t the language of Islam, with its impressive tradition of conquest. It’s the language of the progressive left, of what Jeane Kirkpatrick at the 1984 Republican convention called the “Blame America First” crowd. It fits the left’s view of the West as the perennial sinner and the rest of the world as its perpetual victim. It is the language of turning the page on a decade of war, of focusing on nation building at home.

And so “the moral nihilism of today’s Jihadi Johns is the logical outgrowth of the moral relativism that is the default religion of today’s West.” Excuse me, but what the fuck? In his eagerness to lay the blame for Islamic terrorism at the doorstep of the liberal media and the academic left, Stephens manages to connect “moral relativism,” not with its “logical outgrowth,” but with its logical opposite. Does he or does he not understand that all religious fundamentalism, including radical Islam, is concerned with moral absolutes? Does Stephens let anyone read this crap before it goes into print?

Or is Stephens actually trying to downplay the religious, clash-of-civilizations element of Islamic terrorism—the Manichean, apocalyptic worldview that the WSJ’s chicken hawks have always relied on to gin up support for endless war—in favor of, well, blaming America first? Are ISIS, the poor lambs, merely in thrall to Chomsky and the critical theorists of the American academy? If so, is Stephens suggesting we let Guantanamo’s gates swing wide, while initiating a crackdown on dangerous ideas at home?

I’m sorry, but that is about the dumbest, most confused and self-contradictory piece of shit I have ever read. Let’s give Stephens the benefit of the doubt and assume his epic pundit-fail was brought on by a looming deadline (and maybe also the looming horror of having to vote in the New York Republican primary). Still, not a very good day, even for a not-very-good columnist.

This is the end of the GOP’s Southern strategy. For years, Republicans have courted the white Southerners at the core of the Trump constituency, defended them from attacks on their “culture” of white identity and racial resentment, mimicked their anti-intellectualism—and understood all along that their votes would provide the margin needed to enact the policies of the conservative elite, even if many of those policies (like supply-side economics and neocon foreign policy) have little natural appeal or relevance to working class Southern whites. The GOP even understood that if these voters formed a splinter party (e.g., George Wallace’s AIP), it would be game over for the conservative elite. What the Republican leadership never imagined is that the Trump constituency would actually one day take over the Party.

This could also be the end of identity politics on both the right and the left. My wish—understanding that I may be riding alone on this one—is that Trump’s nomination and resounding loss in November not only will break up the Republican Party (amid general condemnation of all it stands for) but also will wake up the Democratic Party. What I hope for, ultimately, are two reformed parties: one that represents the class interests of the affluent/rich, and one that represents the class interests of the less affluent/poor—and neither of which distracts us with arguments about morality, culture and identity that have no real bearing on our actual material concerns.

What would it be like if every voter made choices solely on the basis of which candidate’s policies would make him or her materially better off, whether measured in terms of, e.g., lower tax and regulatory burdens (on the one side) or, e.g., the availability of social insurance against unemployment, health and retirement risks (on the other side)? Intelligent voters could even take a long-term view of their own material well-being—for example, the affluent/rich could vote for government subsidized health insurance in order to ensure social stability and a supply of healthy workers (or even out of empathy!), and the less affluent/poor could vote to reduce business taxes in order to promote job creation or to incentivize the production of other social goods—without upsetting the basic class equation. With elections focused squarely on class interests and economic outcomes, policies that address the enabling structures of extreme inequality would, at last, be on the table.

What wouldn’t happen in this new two-party system are the false alliances that are made when identity drives politics, and the instability that results when voters are first persuaded, and then unpersuaded, to vote against their own economic interests. Why an end to identity politics? Because the memory of Trump 2016 will be there to remind us what happens.

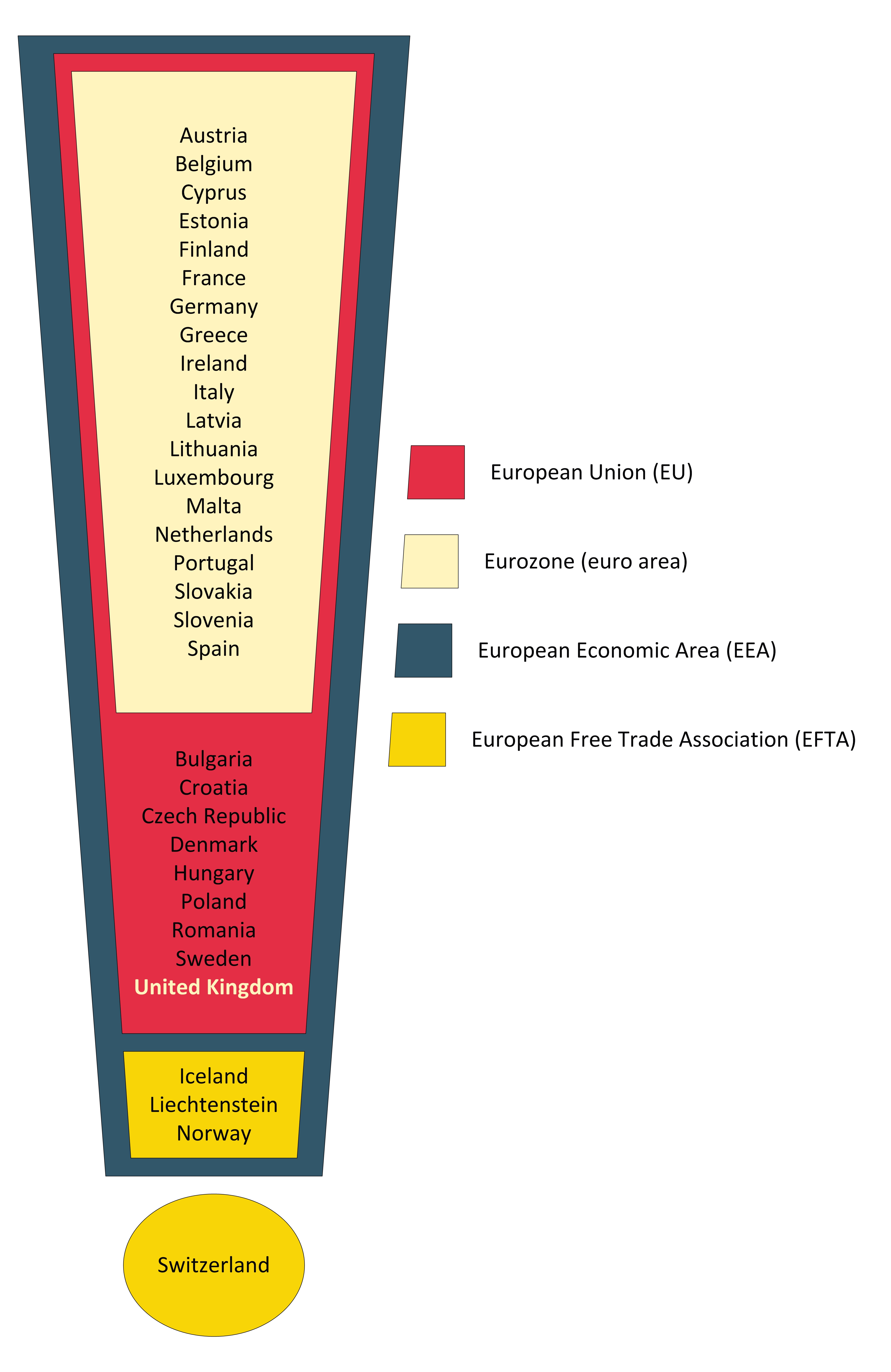

In a Brexit scenario, Britain could end up negotiating EFTA/EEA membership (the “Norwegian option”) or EFTA membership only (the “Swiss option”). Or it could quit the Europe club altogether—unprecedented for an EU member state, albeit not for territorial possessions of a member state (call it the “Greenlandic option”).

Greenland’s melting. Don’t be Greenland, people.

According to a blog post yesterday by Jeff Zients, assistant to the President for economic policy and director of the National Economic Council, President Obama’s fiscal year 2017 budget proposal includes funding of $1.8 billion for the Securities and Exchange Commission and $330 million for the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, up 11% and 32% respectively. More significantly, Zients’ post says that the President is calling for doubling the budgets of the SEC and the CFTC (albeit only from their substantially lower fiscal year 2015 levels) by fiscal year 2021. This has prompted the usual sputtering about excessive regulation and its dolorous effects on economic growth and the price of financial services. Raising barriers to entry in the financial sector. Stifling innovation.

Yadda yadda yadda. As if no serious person would deny the empirical truth of these statements. Far be it from me. But I have some questions:

How much of the 5-year increase in SEC and CFTC rulemaking, examination and enforcement activity will be directed at issuers and end-users (not otherwise engaged in financial activities) and how much will be directed at financial intermediaries (banks, broker-dealers, swap dealers, investment advisers, commodity trading advisers, etc.)?

The growth of the financial sector—particularly in the asset management and household credit sub-sectors—has consistently outpaced GDP growth over the last 35 years, during intervals of both comparatively strict and comparatively permissive financial regulation. To the extent the increased regulatory burdens in the next five years fall on financial intermediaries, what is the evidence that the resulting impediments (if any) to financial sector growth would adversely affect the real economy? That a smaller financial sector might in fact benefit the real economy by releasing some of the human capital and other scarce resources now devoted to extracting rents from the intermediation of financial assets?

The efficiency of the financial sector—as measured by the unit cost of financial intermediation—is today about what it was in 1900. This despite the reduced transaction and other marginal costs resulting from advances in information technology, the use of derivatives to manage risk and the move to an “originate-to-distribute” banking model. Is there any evidence that a 5-year increase in SEC and CFTC rulemaking, examination and enforcement activity would make the financial sector even less efficient and financial intermediation even more expensive, given the insensitivity of unit cost to changes in marginal costs over the very long term?

And if the financial sector’s persistent inefficiency results from the same oligopolistic and other anticompetitive behaviors that seek complex and arbitrary regulation as a means to bar entry and stifle innovation, then wouldn’t it be better to reduce the financial sector’s size and influence (e.g., through antitrust enforcement and campaign finance reform) than to “starve” our only means of goading it into more responsible behavior?