Jim Manzi steps off The Corner and says something truly original about the “effectiveness” debate, an evolutionary argument way smarter than the kind of evidence-free, Saddam-has-WMDs ranting one usually hears in that blighted neighborhood:

Let’s assume arguendo that torture works in the tactical sense that I believe has been used so far in this debate; that is, that one can gain useful information reliably in at least some subset of situations through torture that could not otherwise be obtained. Further, assume that we don’t care about morality per se, only winning: defeating our enemies militarily, and achieving a materially advantaged life for the citizens of the United States. It seems to me that the real question is whether torture works strategically; that is, is the U.S. better able to achieve these objectives by conducting systematic torture as a matter of policy, or by refusing to do this? Given that human society is complex, it’s not clear that tactical efficacy implies strategic efficacy.

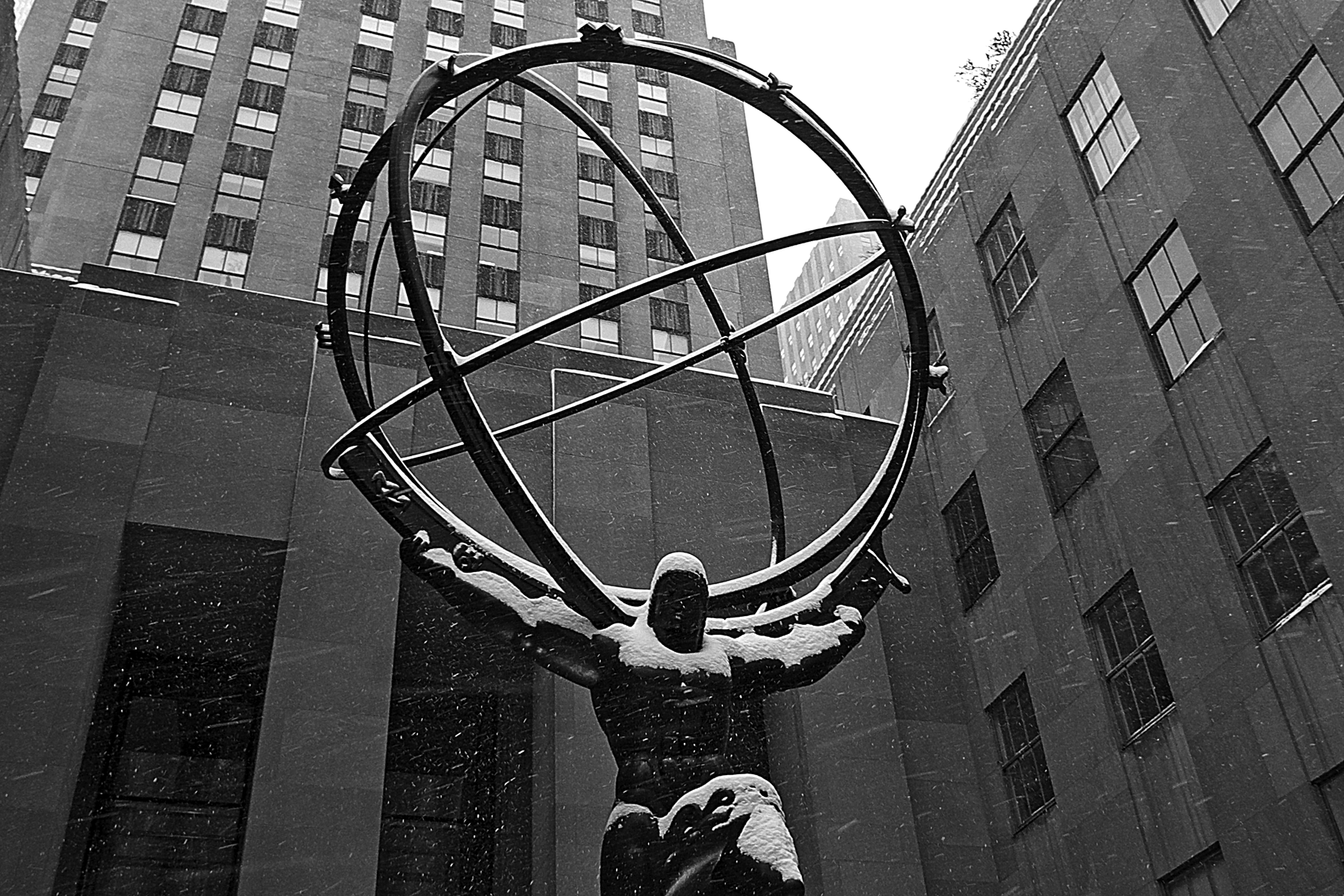

When you ask the question this way, one obvious point stands out: we keep beating the torturing nations. The regimes in the modern world that have used systematic torture and directly threatened the survival of the United States — Nazi Germany, WWII-era Japan, and the Soviet Union — have been annihilated, while we are the world’s leading nation. The list of other torturing nations governed by regimes that would like to do us serious harm, but lack the capacity for this kind of challenge because they are economically underdeveloped (an interesting observation in itself), are not places that most people reading this blog would ever want to live as a typical resident. They have won no competition worth winning. The classically liberal nations of Western Europe, North America, and the Pacific that led the move away from systematic government-sponsored torture are the world’s winners.

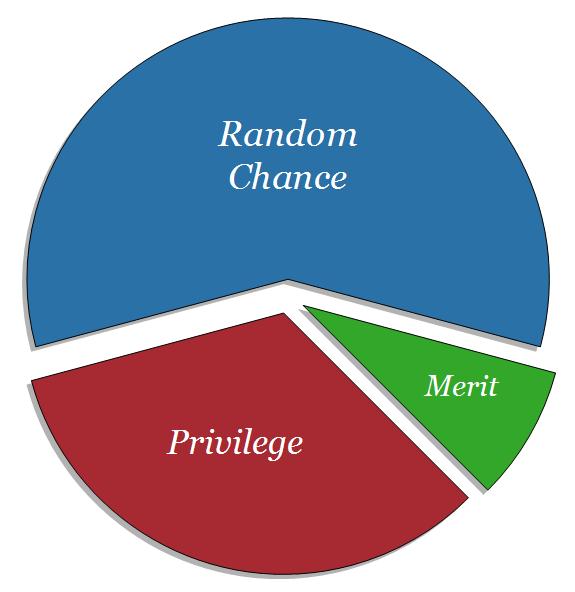

Now, correlation is not causality. Said differently, we might have done even better in WWII and the Cold War had we also engaged in systematic torture as a matter of policy. Further, one could argue that the world is different now: that because of the nature of our enemies, or because of technological developments or whatever, that torture is now strategically advantageous. But I think the burden of proof is on those who would make these arguments, given that they call for overturning what has been an important element of American identity for so many years and through so many conflicts.

Could it be that when Darwinian competition occurs at the level of national systems, “survival of the fittest” means “survival of the most civilized”?

Michael Heizer, North, East, South, West (1967/2002)

Michael Heizer, North, East, South, West (1967/2002)