According to a blog post yesterday by Jeff Zients, assistant to the President for economic policy and director of the National Economic Council, President Obama’s fiscal year 2017 budget proposal includes funding of $1.8 billion for the Securities and Exchange Commission and $330 million for the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, up 11% and 32% respectively. More significantly, Zients’ post says that the President is calling for doubling the budgets of the SEC and the CFTC (albeit only from their substantially lower fiscal year 2015 levels) by fiscal year 2021. This has prompted the usual sputtering about excessive regulation and its dolorous effects on economic growth and the price of financial services. Raising barriers to entry in the financial sector. Stifling innovation.

Yadda yadda yadda. As if no serious person would deny the empirical truth of these statements. Far be it from me. But I have some questions:

How much of the 5-year increase in SEC and CFTC rulemaking, examination and enforcement activity will be directed at issuers and end-users (not otherwise engaged in financial activities) and how much will be directed at financial intermediaries (banks, broker-dealers, swap dealers, investment advisers, commodity trading advisers, etc.)?

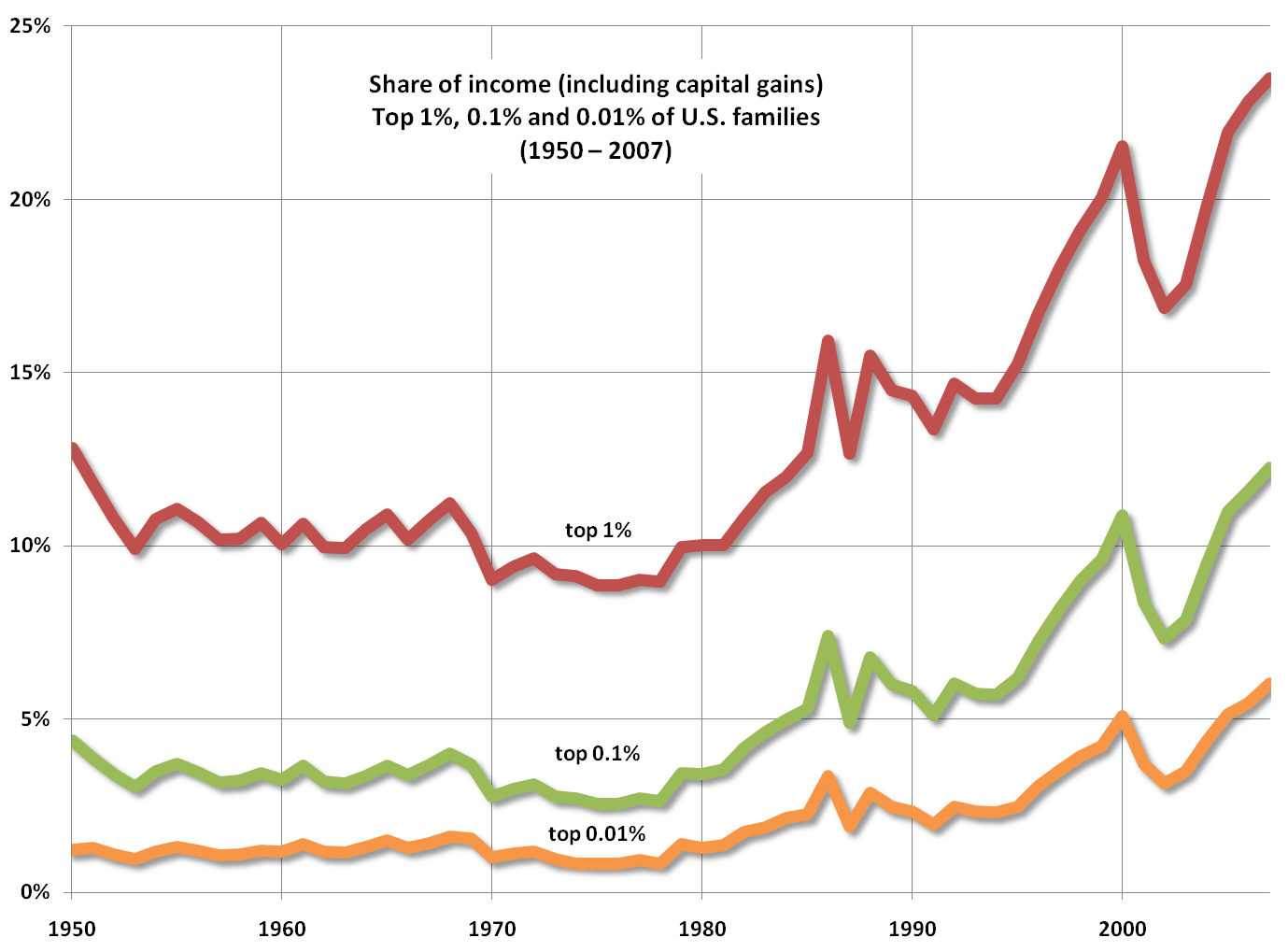

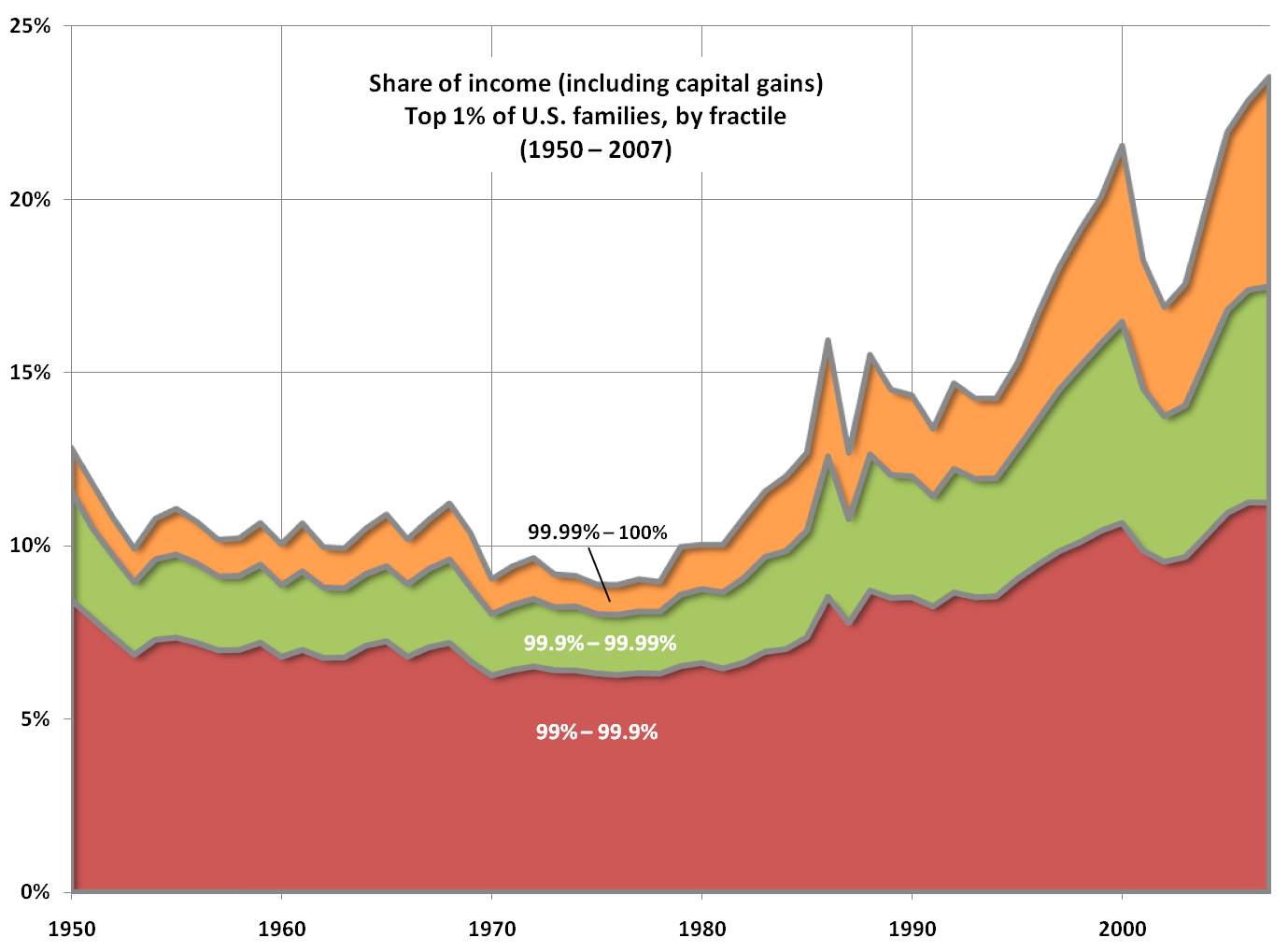

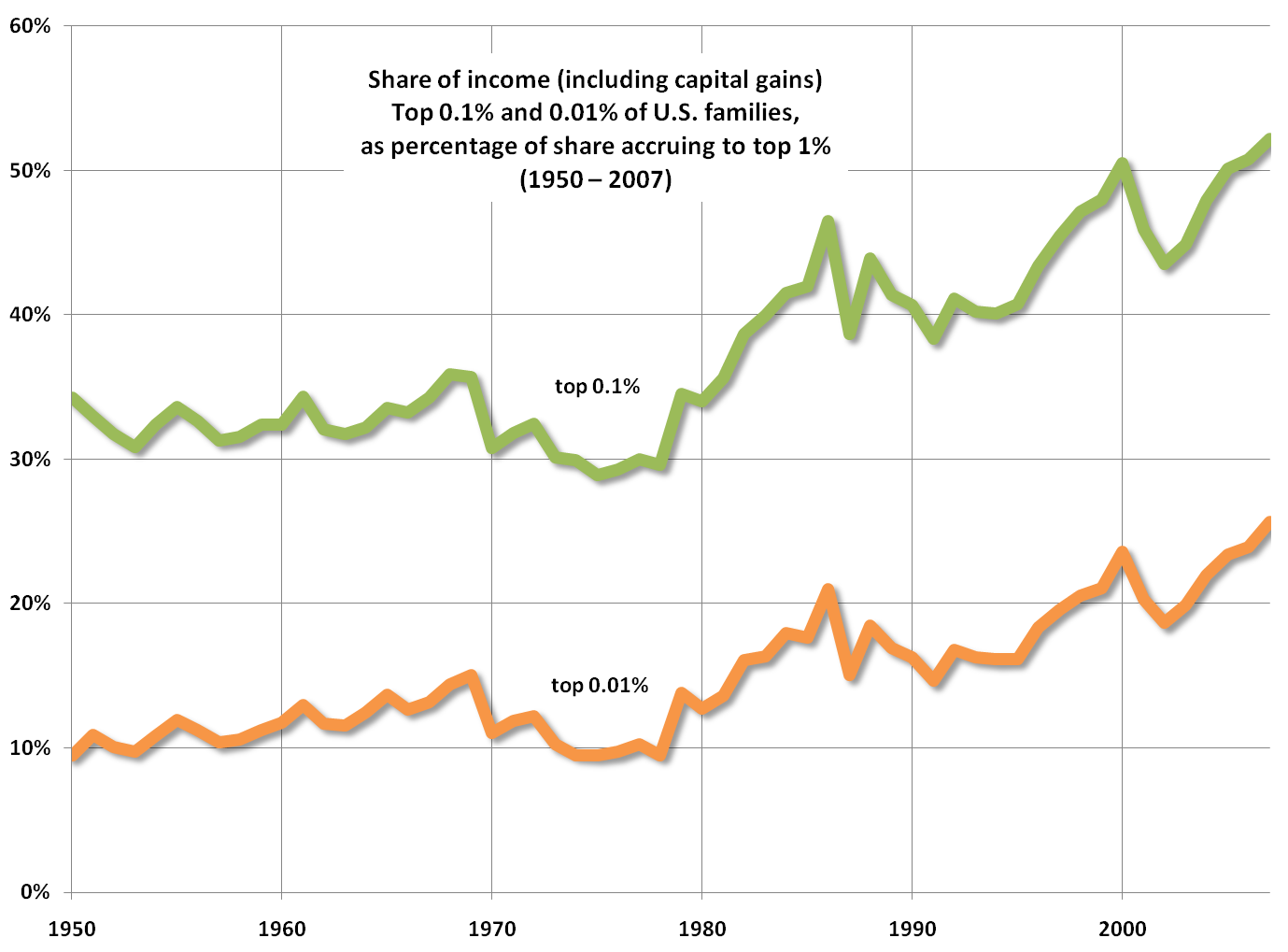

The growth of the financial sector—particularly in the asset management and household credit sub-sectors—has consistently outpaced GDP growth over the last 35 years, during intervals of both comparatively strict and comparatively permissive financial regulation. To the extent the increased regulatory burdens in the next five years fall on financial intermediaries, what is the evidence that the resulting impediments (if any) to financial sector growth would adversely affect the real economy? That a smaller financial sector might in fact benefit the real economy by releasing some of the human capital and other scarce resources now devoted to extracting rents from the intermediation of financial assets?

The efficiency of the financial sector—as measured by the unit cost of financial intermediation—is today about what it was in 1900. This despite the reduced transaction and other marginal costs resulting from advances in information technology, the use of derivatives to manage risk and the move to an “originate-to-distribute” banking model. Is there any evidence that a 5-year increase in SEC and CFTC rulemaking, examination and enforcement activity would make the financial sector even less efficient and financial intermediation even more expensive, given the insensitivity of unit cost to changes in marginal costs over the very long term?

And if the financial sector’s persistent inefficiency results from the same oligopolistic and other anticompetitive behaviors that seek complex and arbitrary regulation as a means to bar entry and stifle innovation, then wouldn’t it be better to reduce the financial sector’s size and influence (e.g., through antitrust enforcement and campaign finance reform) than to “starve” our only means of goading it into more responsible behavior?