Law

Post-election outreach to clients—what’s really at stake?

I’ve been asked what it was that made me so uncomfortable about putting out a standard post-election memorandum to clients describing potential regulatory changes under the new Administration. I’ll get to that in a moment. Now, it’s time for us to heal the bitter divisions, join together as one nation, and consider how we defend our country, our clients and ourselves from the dangerous tyrant we just elected President.

Donald Trump—President Donald Trump!—threatens national security and menaces the rule of law. By his own statements, anyone can see that the man stands far outside the norms that have guided our democracy and its leaders for 240 years. He’s functionally illiterate and may be uneducable. He appears to have a range of diagnosable personality disorders.

This is not just me on a rant. This is a widespread, bipartisan, across-the-spectrum opinion. The only thing the people who hold this view have in common is an ability to see a picture of the national interest bigger than the potential for career advancement or revenue opportunities.

And yet here we are, only three days after the election and already entering the “normalization” phase: the President-elect sits down with the President, the First Lady-elect has tea with the First Lady, there is news of transition teams and cabinet appointments, and law firms talk to clients about legislative and policy initiatives to expect from the incoming Administration.

That’s what made me so uncomfortable about publishing a standard post-election client memo. By treating this like any other Presidential transition from one political party to the other, the memo would have helped (albeit unintentionally) to normalize Trump and, as a result, would have misled our clients about what they really have at stake.

■

Most of our clients are participants in regulated markets of one kind or another and, as we all know, have made the management of regulatory risks and enforcement risks a core element of their strategies and a key driver in almost every decision-making process.* The regulatory risks (or perhaps I should say benefits) posed by the incoming Trump Administration may well be more or less what you’d expect from a conventionally conservative Republican-led government that stands for lower taxes and rising sea levels, and so our clients may feel free to mutter “excellent” while steepling their fingers, Mr. Burns style.

Most of our clients are participants in regulated markets of one kind or another and, as we all know, have made the management of regulatory risks and enforcement risks a core element of their strategies and a key driver in almost every decision-making process.* The regulatory risks (or perhaps I should say benefits) posed by the incoming Trump Administration may well be more or less what you’d expect from a conventionally conservative Republican-led government that stands for lower taxes and rising sea levels, and so our clients may feel free to mutter “excellent” while steepling their fingers, Mr. Burns style.

The enforcement risks are another matter entirely.

I’ll cut to the chase. The single most salient thing we can say to our clients about the incoming Trump Administration is that investigative and prosecutorial discretion—and the degree to which firms need to factor into their risk management protocols the potential for abuse of that discretion—may be about to change, big-time.

Donald Trump has already made very clear his interest in the retaliatory potential of the Presidency. He has already announced an intention to use his executive power to punish his opponents and critics; already suggested that he would order the Department of Justice and various other agencies of the Federal government’s administrative and law enforcement apparatus to abuse their investigative and prosecutorial discretion by targeting his enemies. That is what Trump has said. Is it unfair or unseemly to take the President-elect at his word?

Above almost all else, our clients depend on the rule of law. The possibility of investigative or prosecutorial misconduct—that is, the chance that firms could become the targets of investigations or enforcement proceedings arbitrarily and for reasons unrelated to their regulatory compliance record—makes it exceedingly difficult for our clients to manage enforcement risks on any rational, cost/benefit basis. Adding to the costs of prosecutorial misconduct are the various collateral consequences that increasingly attach to enforcement determinations and the profound disruptions that even a civil investigation can cause for many firms in regulated industries.

I think we owe our clients an even-tempered evaluation of the possibility, based on widely reported statements, that the Trump Administration would commit abuses of investigative and prosecutorial discretion by targeting individual firms or entire industry sectors on a retaliatory basis. We should include a summary of the Federal government’s institutional defenses against such abuses, from the investigative guidelines adopted by past Attorneys General and the rules against White House interference in DOJ decision-making to the institutional cultures of the DOJ and other Federal law enforcement agencies. We should be frank about how fragile those institutional defenses may be when under sustained attack.

A memo like this would be far more valuable to our clients than the usual “what to expect from the new Administration” fare. And I think we would get some very positive feedback and high scores for originality and daring. Best of all, we would ensure that our Firm does its part to keep Donald Trump on the far side of normal where he belongs until, at long last, he resigns or is impeached.

■

Go ahead, call me hysterical. But when the history of this awful chapter is written, big-firm lawyers will be Exhibit A in the account of how Trump was “normalized” after the election and how the rule of law was left unattended and at risk. Maybe that’s what we’ve become. Standing on abstract principles like “rule of law” is so last-century; we have a business to run and our commercial interests appear best served by speaking sweetly to power. Big-firm lawyers aren’t alone, of course: all the other professional service businesses that comprise the flattering classes, all of us whose primary function is to protect and defend the wealth of others, seem to have the same means of self-preservation. We assume no one would want us to focus on long- or even medium-term risks to fundamental rights or the rule of law—not when tax cuts and financial deregulation are right around the corner. So we normalize the greater threat and hype the “opportunities” for our clients. I guess we’ll see what happens next.

* For present purposes, when I say “regulatory risks” I mean the risks that the adoption of new or amended Federal laws, regulations and agency interpretations will affect a client’s costs of engaging in regulated activities. When I say “enforcement risks,” on the other hand, I mean the risks that a client’s compliance with existing Federal laws, regulations and agency interpretations will become the subject of an investigation or enforcement proceeding brought before a Federal administrative or law enforcement agency and, in cases of alleged criminal violations, referred to the US Department of Justice.

Do the Brits really not care to belong to any club that would have them as a member?

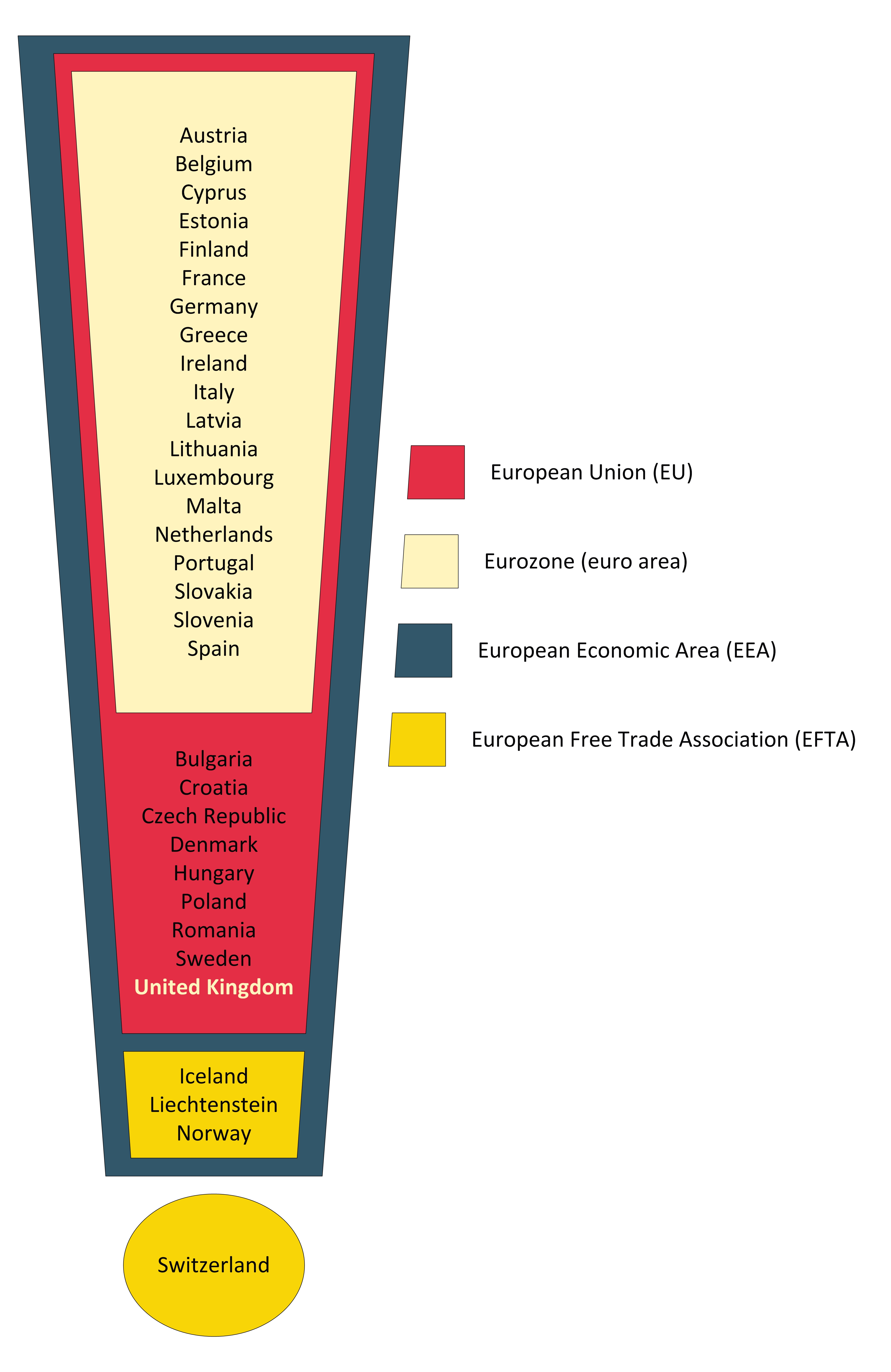

In a Brexit scenario, Britain could end up negotiating EFTA/EEA membership (the “Norwegian option”) or EFTA membership only (the “Swiss option”). Or it could quit the Europe club altogether—unprecedented for an EU member state, albeit not for territorial possessions of a member state (call it the “Greenlandic option”).

Greenland’s melting. Don’t be Greenland, people.

Doubling the SEC and CFTC budgets

According to a blog post yesterday by Jeff Zients, assistant to the President for economic policy and director of the National Economic Council, President Obama’s fiscal year 2017 budget proposal includes funding of $1.8 billion for the Securities and Exchange Commission and $330 million for the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, up 11% and 32% respectively. More significantly, Zients’ post says that the President is calling for doubling the budgets of the SEC and the CFTC (albeit only from their substantially lower fiscal year 2015 levels) by fiscal year 2021. This has prompted the usual sputtering about excessive regulation and its dolorous effects on economic growth and the price of financial services. Raising barriers to entry in the financial sector. Stifling innovation.

Yadda yadda yadda. As if no serious person would deny the empirical truth of these statements. Far be it from me. But I have some questions:

How much of the 5-year increase in SEC and CFTC rulemaking, examination and enforcement activity will be directed at issuers and end-users (not otherwise engaged in financial activities) and how much will be directed at financial intermediaries (banks, broker-dealers, swap dealers, investment advisers, commodity trading advisers, etc.)?

The growth of the financial sector—particularly in the asset management and household credit sub-sectors—has consistently outpaced GDP growth over the last 35 years, during intervals of both comparatively strict and comparatively permissive financial regulation. To the extent the increased regulatory burdens in the next five years fall on financial intermediaries, what is the evidence that the resulting impediments (if any) to financial sector growth would adversely affect the real economy? That a smaller financial sector might in fact benefit the real economy by releasing some of the human capital and other scarce resources now devoted to extracting rents from the intermediation of financial assets?

The efficiency of the financial sector—as measured by the unit cost of financial intermediation—is today about what it was in 1900. This despite the reduced transaction and other marginal costs resulting from advances in information technology, the use of derivatives to manage risk and the move to an “originate-to-distribute” banking model. Is there any evidence that a 5-year increase in SEC and CFTC rulemaking, examination and enforcement activity would make the financial sector even less efficient and financial intermediation even more expensive, given the insensitivity of unit cost to changes in marginal costs over the very long term?

And if the financial sector’s persistent inefficiency results from the same oligopolistic and other anticompetitive behaviors that seek complex and arbitrary regulation as a means to bar entry and stifle innovation, then wouldn’t it be better to reduce the financial sector’s size and influence (e.g., through antitrust enforcement and campaign finance reform) than to “starve” our only means of goading it into more responsible behavior?

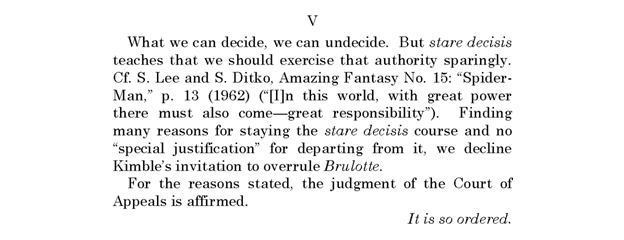

Spidey decisis

The final paragraphs of this morning’s opinion of the Supreme Court in Kimble v. Marvel Entertainment, LLC—a patent case involving Spider-Man web-shooters—in which the Court’s decision turned on whether it would overrule its prior decision in Brulotte v. Thys Co., 379 U.S. 29 (1964):

One of Justice Kagan’s clerks is having a really, really good day today.

Good textualism vs. bad textualism

Around here, the reaction to President Obama’s speech at the Catholic Health Association conference a couple of days ago, where the President called out the “cynicism” underlying the petitioners’ claims in King v. Burwell – being the second attempt by die-hard Obamacare opponents to recruit five willing executioners on the Supreme Court – was nothing short of hysterical. In addition to the usual attacks on the President’s disrespect for the rule of law and Nietzschean impulses, there was renewed finger-wagging to the effect that the language in dispute is not a “a drafting error or a typo” but rather stands on its own as wholly dispositive of the matter at hand.

So, while we wait for the ruling to come down, let’s read the amicus curiae brief filed by Eskridge, et al., and see statutory interpretation done as God and Oliver Wendell Holmes intended. The introduction and summary of argument:

The court of appeals held that the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) does not prohibit the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) from providing tax credits to individuals who purchase health insurance on exchanges created by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Petitioners challenge that conclusion on the sole ground that seven words in 26 U.S.C. § 36B – “established by the State under section 1311” – foreclose tax credits on HHS-created exchanges. The text, they say, is clear, so by holding otherwise, the court below elevated statutory purpose over statutory text.

But this is not, as Petitioners suggest, a case about textualism vs. purposivism. It is a case about good textual analysis vs. bad textual analysis. Textualism does not require courts to read statutory provisions in a vacuum. To the contrary, it is a “fundamental canon of statutory construction that the words of a statute must be read in their context and with a view to their place in the overall statutory scheme.” FDA v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 529 U.S. 120, 133 (2000) (internal quotation marks omitted). By focusing exclusively on Section 36B’s seven words in isolation, Petitioners violate textualism’s core tenets and adopt an interpretation that would nullify the Act as a whole.

Modern textualism developed as a response to purposivism, which held that the letter of the law must yield to legislative “intent.” A search for legislative intent, textualists have explained, violates the constitutionally prescribed process of bicameralism and presentment: The only “law” to interpret is the text of a statute passed by both houses of Congress and signed by the president. By combing the legislative history for indicia of legislative intent, moreover, purposivist analysis risks substituting judicial judgment for the judgment of Congress. Thus, by focusing on the text of a statute – rather than on ethereal notions of legislative “intent” – textualism cabins judicial discretion, respects legislative supremacy in the policymaking process, and renders the interpretive process more predictable.

But textualism is not hyperliteralism, and textualists do not read the words of a statute in a vacuum. To the contrary, “reasonable statutory interpretation must account for both ‘the specific context in which … language is used’ and ‘the broader context of the statute as a whole.’” Utility Air Regulatory Grp. v. EPA, 134 S. Ct. 2427, 2442 (2014) (quoting Robinson v. Shell Oil Co., 519 U.S. 337, 341 (1997)). Thus, a statutory phrase that has one apparent meaning when read in isolation may have a different meaning when read in the context of the statute as a whole.

King v. Burwell – place bets gentlemen

Before oral arguments even begin this morning, I’m going to go way the hell out on a limb and predict the final outcome.

It will be 5-4 in favor of the government. Either (i) Roberts will write the opinion of the Court, joined by Breyer, Ginsburg, Kagan and Sotomayor, or (ii) there will be no majority opinion, with Alito, Kennedy, Scalia and Thomas on one side, Breyer, Ginsburg, Kagan and Sotomayor on the other, and Roberts siding with the government but writing only for himself. There is a slight possibility that Kennedy would join a majority opinion, leaving Roberts free to hang with the boys, but I’m counting on him to flake out with a literalist approach to the statutory language.

I take it as a given that Chevron deference to agency interpretation is a dead letter with the Court’s right wing, at least when the agency is the IRS and a Democrat is in the White House. But the more interesting discussion – which I expect to dominate today’s argument – is around Constitutional federalism and the Pennhurst doctrine, basically the idea that if Congress is going to place conditions on States’ entitlement to federal funding, it had better do so clearly and unambiguously, sort of like an “actual notice” requirement. Whatever else those four words in 26 U.S.C. § 36B may mean to a committed textualist, no one can seriously claim that Section 36B put States on Pennhurst-worthy notice that they would lose Obamacare subsidies if they didn’t set up their own exchanges. But since Alito, Scalia and Thomas have given up on being serious, that is probably what they will in fact claim.

Again assuming that Kennedy joins the nihilists, I think Roberts will use Pennhurst to thread the needle, prevent a humanitarian disaster and, once again, be the lonely steward of the Court’s reputation. His one-man opinion will uphold the IRS regulations, essentially by saying that if the IRS had instead withheld Obamacare subsidies from states that didn’t set up their own exchanges, it would have violated principles of Constitutional federalism under Pennhurst. The four liberal Justices may join Roberts’ opinion (making it an opinion of the Court), but I think it’s at least as likely that they will write their own opinion, basically on Chevron or general “don’t waste my time with this nonsense” grounds. The main reason I think that may happen is because Roberts will go a little too far with his Pennhurst logic in an attempt to snatch a conservative victory from the jaws of Obamacare defeat, and try to sneak in a brand new way for States to challenge federal mandates. (That federalism stuff is dangerous, I tell you.) So Roberts will be on his own, much as he was with his taxing power argument in NFIB v. Sebelius.

Well. Now I’m feeling exposed. Still, I hope I’m right. All this nifty argumentation aside, if the challengers win this one, with full knowledge of how many people will die as a direct result, they’re not just vandals – they’re terrorists.